The Human Supply Chain Breakdown

There’s a strange contradiction in how we think about extraction. Historically, we look back on colonialism as one of the most exploitative, morally bankrupt acts, taking resources from one place, moving them to another, and consolidating wealth in the hands of the few. We see it as theft, a destruction of local economies, countries and the life of people, a short-sighted act that created long-term instability. And yet, in the modern world, we celebrate a different kind of extraction, the movement of human capital.

Bringing the best minds into a country is viewed as progress. There is no moral outcry when a developing nation’s most brilliant engineers, doctors, or scientists leave for better pay, infrastructure, and opportunities in the U.S. or Europe. God knows I am grateful for this being a first-generation immigrant in the US. It’s seen as generosity, offering talented individuals a chance at a better life. But what happens to the places they leave behind? What happens when the structure that once produced excellence starts to collapse because there is no one left to build within it?

It’s a shift in what we value. In an industrial economy, physical resources were the bottleneck. Now, in a world defined by services, technology, and knowledge, the real wealth lies in expertise, in intellectual capital. And we are just as careless in how we handle it.

This becomes even more apparent when we consider the way companies have restructured work over the last few decades. There was a time when businesses hired entry-level employees, trained them, mentored them, built them into experts over years and decades. They invested in people. But somewhere along the way, that changed. Companies no longer want to develop talent, they want to extract it, fully formed, from wherever they can find it cheapest. Instead of building capability, they buy it as a commodity. And if it’s cheaper overseas, they send the work there.

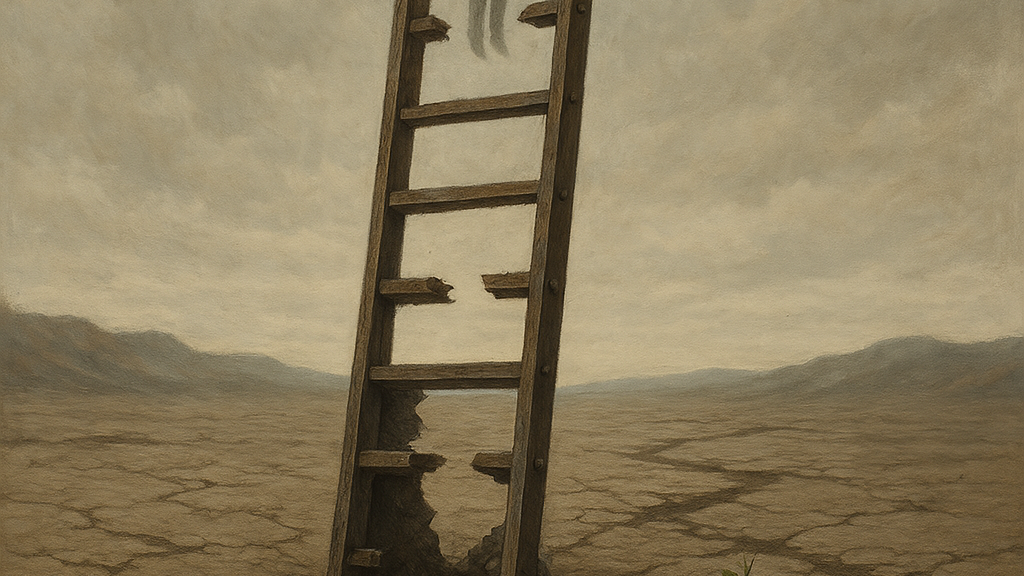

The problem is, no one thinks about what is lost. The short-term efficiency of outsourcing low-level work comes at the cost of an entire generation missing the opportunity to learn. If all the grunt work, the kind of work that builds discipline, attention to detail, and an intuitive sense of an industry, is offloaded elsewhere, what happens when those workers retire? Where does the next generation of experts come from?

This is the blind spot in how we talk about automation, outsourcing, and efficiency. Everyone is focused on the immediate cost savings, the higher margins, the streamlined operations. But no one is asking the deeper question: If entry-level work disappears, if entire functions are pushed offshore, what does that mean for the long-term sustainability of knowledge?

We are quick to acknowledge that experience compounds, that the best solutions come from those who have spent years wrestling with a problem, testing ideas, refining their craft. And yet we are systematically dismantling the very pathway that allows people to reach that level of expertise. We aren’t just outsourcing work; we are outsourcing the process of learning itself.

And yet, when we talk about bringing manufacturing back to the U.S., it’s treated as a critical issue of national interest. There is broad agreement that we shouldn’t be entirely dependent on foreign supply chains and that we should invest in domestic production, even if it’s not the most cost-efficient choice in the short term, that is fair enough. But when it comes to human labor—when it comes to the training and development of people, the same logic isn’t applied. There are no tariffs on outsourcing talent. No penalties for eroding a country’s ability to grow its own experts. In fact, the opposite is true: companies are rewarded for cutting costs, for reducing payroll, for shifting as much work as possible to the cheapest bidder.

What’s even more bizarre is that this shift is happening at the same time as AI is advancing rapidly. If anything, the argument for keeping work local has never been stronger. The same efficiency gains that once made outsourcing attractive can now be achieved through automation and better tools. A single well-trained employee, equipped with the right AI systems, can be as productive as five people doing the same job manually. This isn’t theory, it’s already happening. The problem is, companies are using these tools purely as cost-cutting mechanisms rather than as a way to rethink the workforce entirely.

The most powerful organizations in the coming decades won’t be the ones that simply find the cheapest labor or the lowest costs. They will be the ones that invest in their own capability. The ones that don’t just extract value, but build systems where knowledge and expertise can compound over time.

There is a point where efficiency turns into fragility. Where cost-cutting turns into dependence. And where outsourcing stops being about smart business and starts being about a quiet erosion of the very structures that create long-term success. This isn’t just an economic issue, it’s an issue of how we think about value itself.

Share this post: